-

Product Management

Software Testing

Technology Consulting

-

Multi-Vendor Marketplace

Online StoreCreate an online store with unique design and features at minimal cost using our MarketAge solutionCustom MarketplaceGet a unique, scalable, and cost-effective online marketplace with minimum time to marketTelemedicine SoftwareGet a cost-efficient, HIPAA-compliant telemedicine solution tailored to your facility's requirementsChat AppGet a customizable chat solution to connect users across multiple apps and platformsCustom Booking SystemImprove your business operations and expand to new markets with our appointment booking solutionVideo ConferencingAdjust our video conferencing solution for your business needsFor EnterpriseScale, automate, and improve business processes in your enterprise with our custom software solutionsFor StartupsTurn your startup ideas into viable, value-driven, and commercially successful software solutions -

-

- Case Studies

- Blog

Most Basic Git Commands with Examples

"Hello, Git! I hate you already!"

Most of us dislike Git on the first try even after running the most basic Git commands. Having a Git cheat sheet taped to our table doesn't help. Git is very complicated, as you can't learn all its concepts by just using it.

Sadly, your life as a web developer will also be complicated without Git, and here's why.

The #1 problem of life without Git is that you can't adequately manage project versions. When you start a new project, you create several basic files. These basic files constitute the first version of your application. But the next day you develop the first feature, and thus you create a second version of the app. Still later, you decide to rework the first feature. Therefore, you create a third version of your app.

When you remove or rework code, you can't restore its previous state (read: version). Without Git, you'd have to save each version of the project to a different place. Restoring a project from several places, however, isn't a viable option. How can you know which exact app version is the one you need? Git, on the other hand, can tell you what project version you're restoring.

Here's another problem of development without Git: several developers will work on the same project, and they'll also need access to previous app versions. How can you share your code with the entire development team?

I can use Dropbox, Google Drive, OneDrive, a flash drive… any other drive to store my code and share it with everyone!

That's true. But again, how can you know for sure which version of code is the latest? And if your friend wants to merge your code with his version in the same file, would you like to go line by line to see whose code will be merged into which part of a file? We bet you wouldn't.

Git easily solves both problems we've described: managing project versions and sharing code among developers. But to make Git our best friend, we should understand how Git works. To do so, we should also start using basic Git commands.

What's Git?

Git is a distributed version control system (DVCS). "Distributed" means that all developers within a team have a complete version of the project. A version control system is simply software that lets you effectively manage application versions. Thanks to Git, you'll be able to do the following:

- Keep track of all files in a project

- Record any changes to project files

- Restore previous versions of files

- Compare and analyze code

- Merge code from different computers and different team members.

These capabilities listed above don't tell how Git actually works, however. In all its complexity, Git works quite simply: you first need to create a local repository in your project's root directory (folder). Afterwards, Git can track project files and directories and add them to the repository. You may be thinking, "Not again! We're talking about a repository now?"

I know who did what, when, and why.

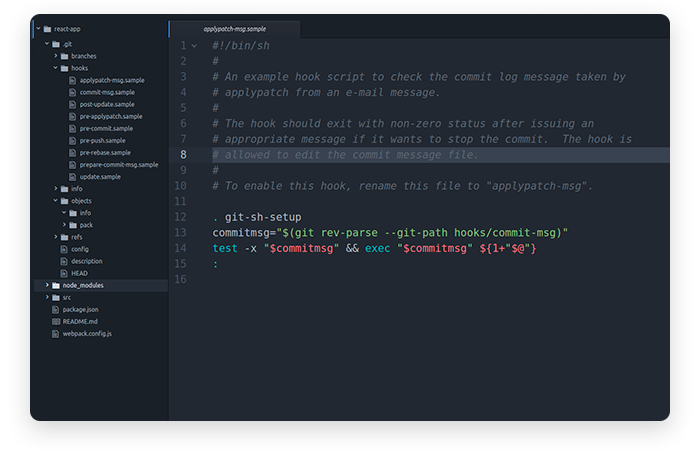

A repository is just a directory (a folder) in your project's root directory. (Throughout the entire article we'll use the term directory, not folder.) You can't see repositories in your filesystem as they're hidden. But you can still see a repository in your code editor or IDE:

What's a local repository? Let's use our imagination to understand repositories.

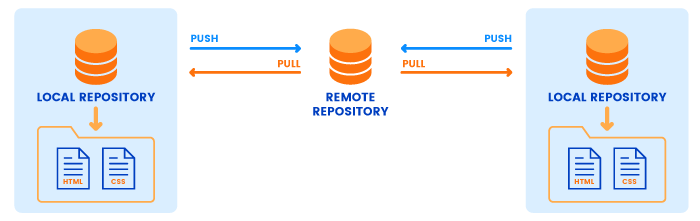

If you store your stuff (code) at home (on a computer with a Git directory), you store your stuff locally. So a repository on your own computer will be called local. A remote repository is like a public storehouse located in a different building. You may have heard about remote repositories such as GitHub, BitBucket, and GitLab. They're like storehouses for code. Thanks to Git, you can copy your entire project to a remote repository while keeping it in a local repository as well.

Why do we use local and remote repositories? Let's explain a little bit.

In the real world, you can't have exactly the same stuff at home and in a storehouse. If your things disappear from home (God forbid!), you'll be able to recover copies or clones (at best) from a storehouse. And you'll still lose some valuables (the original things). With GitHub or BitBucket, however, it's a different story.

Remote storehouses (repositories like GitHub or BitBucket) store exactly the same code that you have in your local repository (on your home computer). If your code disappears from your local repository, you can restore absolutely the same code from a remote repository. A remote repository also serves as a central hub to which members of a web development team can connect to access project code.

By now it should be clear what Git is and what repositories are. But we also need to mention two methods to run Git commands. You can use programs with graphical user interfaces for Git. But you can also run terminal commands for Git. The terminal will be your paper on which you'll write Git commands. For the purpose of this article, we'll use the terminal (also called the command line) to run Git commands. The terminal is a basic tool that all developers should understand.

Lastly, you need to install Git on your computer. Follow these instructions if you haven't done that already. Once you have Git installed, you can move on to basic Git commands with examples to make friends with Git. You can consider the following sections a Git tutorial.

Configuring Git

When you come to a bank for the first time and ask to store your money there, they give you a bunch of paperwork to fill out. Before you can use banking services, you have to register with the bank. Git wants you to do the same (register with Git) before you start using a repository.

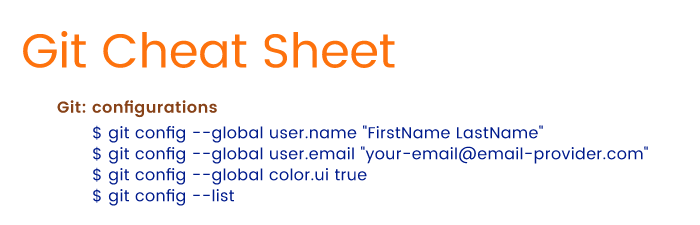

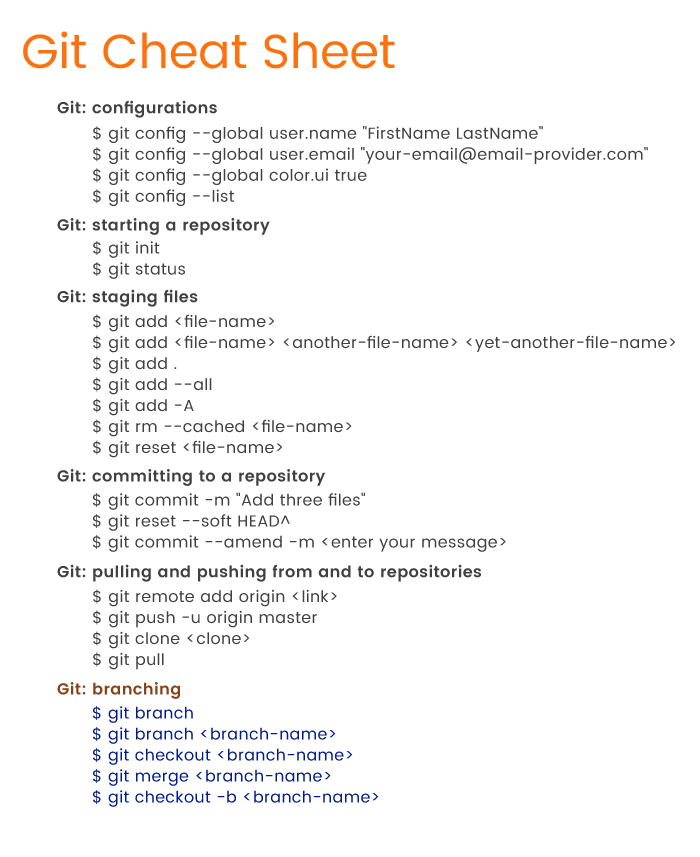

To tell Git who you are, run the following two commands:

You've completed the first configurations! (Hopefully you've registered your real name and email. If not, you can easily change them by running the same commands once more, but using your real name and email this time.)

Let's quickly review the syntax of Git commands. You first need to type "git", followed by a command – "config" in our example – and pass an option, which is "--global" in the code above. The option "--global" means that you set your username and email for Git globally on your computer. No matter how many projects with separate local repositories you create, Git will use the same username and email to mark your commits.

There's one thing to configure before you start using Git. Since you'll see the output from many Git commands in the terminal, it's best to have some pretty colors for the output. To turn on code highlighting, just run the following command:

Again, this configuration will be applied globally and it tells Git to highlight words in the terminal output to improve readability.

The last basic configuration command will let you view your Git configurations. Running this command is the same as asking for a copy of your contract:

That's enough for a start. You've got the feeling of Git by running several simple configuration commands. But you haven't actually used Git yet. Let's try some real Git, so to speak.

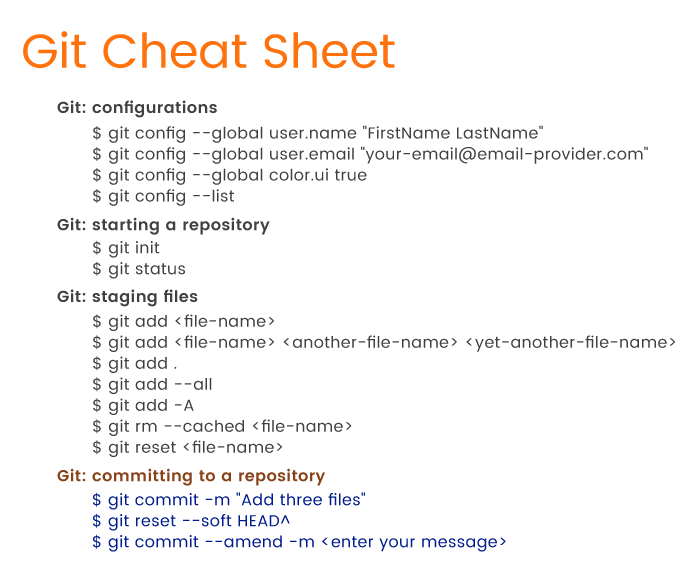

We'll finish each section with a Git commands list. Here are the basic Git commands you've learned so far:

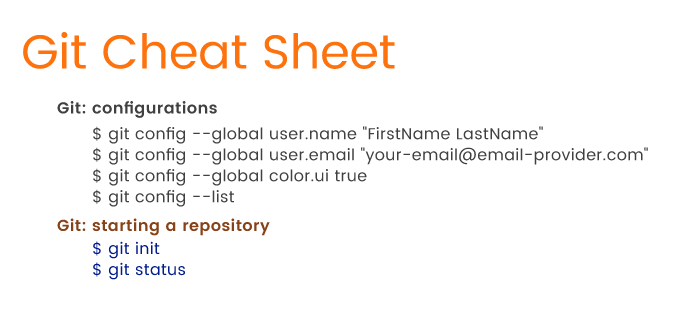

Starting a New Local Repository with Git

To continue with our bank metaphor, we need to explicitly ask the bank to open a new safe deposit box to store our effects (read: code). Assuming you've already created an empty directory for your project, you need to explicitly ask Git to create a safe deposit box – a repository – in that directory:

The "init" command stands for initialize. Once you run "git init", Git will initialize a hidden directory called ".git" in the project's root directory. And you'll get a confirmation that your deposit box is ready! What's next? You might want to know the status of your box: does it store anything yet? To know the Git status, you'll need to run:

You'll run the command "git status" quite often. It's the same as calling a bank administrator to check if your things arrived or if anything has been moved to a different vault.

For now, Git will give you the following output:

The message above presents a few new terms, so let's clarify what they mean.

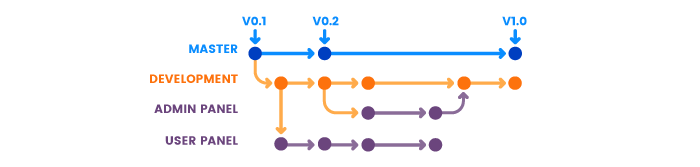

Git Branches

You can consider branches in Git as paths. Imagine that you explore a new territory and you mark the main path to water with poles each 10 to 15 meters. This main path is like the master branch, and the poles are like commits. We'll talk more about branches in the last section of the article. For now, it's sufficient to know that Git has a base branch called the master branch.

Git Commits

A commit to a repository is a snapshot of the current state of the project's root directory. Since this explanation doesn't really tell anything, we need to delineate the underlying concept.

Let's say you're working with a bunch of papers. You've written ten texts about animals on separate sheets of paper and you want to note what texts they are and when you wrote them. You take out another sheet of paper, call it a "commit," and write on this commit paper: "I've written text #1. It's about birds. I've written text #2. It's about dogs..." Then you create a copy of each text. The last thing you do is you gather those ten copies, pin the commit paper on top of them, and lay them in a drawer.

The next day you rewrite the original texts, then get the copies from your drawer and compare the texts. This is basically what Git does. You create files and write code in them. When you're ready, you commit your files to a repository: you create copies of files and lay them in a drawer (a repository). (Our inner nerd wants to specify that Git doesn't actually push copies of files to the repository; Git creates a light representation of the project files for performance benefits.)

Each day you write that commit message and add new texts. Git creates a history of your commits, so you can trace back to the very beginning of the project development to see what files have been changed or added, who added or changed them, and when.

Tracking Files with Git

Now we can answer the question, "Why does Git need to track files?" Before we commit any files to a local repository, Git wants to know what those files are. Git only knows what to commit when it's tracking files.

We've explained three basic Git concepts you need to know, but we've also moved far away from explaining Git commands. Nevertheless, it's crucial to grasp Git's basic concepts to understand how Git commands work. Now that we've explained the meaning of Git concepts, we can get back to the commands.

Let's remind you what output you'll see after you run "git status" for the first time:

Since there are no files in the root directory yet, Git shows that there's nothing to commit. Our safe deposit box (repository) is empty. To do anything further, we need to populate the root folder with at least one file. We've added my-new-file.txt to the root directory. Now we can move on to the next step.

When you run "git status" once more (assuming you've added a file to the project's root directory), you'll get a different output:

Note the "Untracked files" message with the file "my_new_file.txt". Git conveniently informs us that we've added a new file to the project. But that isn't enough for Git. As Git tells us, we need to track "my_new_file.txt". In other words, we need to add "my_new_file.txt" to the staging area. The following section will uncover the basic Git commands for working with the staging area.

Here are the basic Git commands you've learned so far:

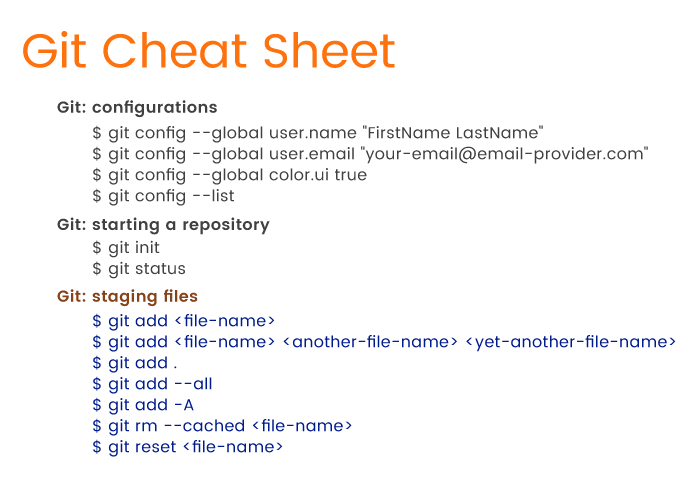

Staging Files with Git

Before we cover simple Git commands used for staging files, we need to explain what the staging area is.

Let's say you want to move some of your valuable effects to a lock box, but you don't know yet what things you'll put there. For now, you just gather things into a basket. You can take things out of the basket if you decide that they aren't valuable enough to store in a lock box, and you can add things to the basket as you wish. With Git, this basket is the staging area. When you move files to the staging area in Git, you actually gather and prepare files for Git before committing them to the local repository.

To let Git track files for a commit, we need to run the following in the terminal:

That's it; you've added a file to the staging area with the "add" command. Don't forget to pass a filename to this command so Git knows which file to track.

But what has this "add" command actually done? Let's view an updated status (we promised that you'll often run "git status", didn't we?):

The status has changed! Git knows that there's a newly created file in your basket (the staging area), and is ready to commit the file. We'll get to committing files in the next section. For now, we want to talk more about the "git add" command.

What if you create or change several files? With a basket as your staging area, you have to put things into the basket one by one. Committing files to the repository individually isn't convenient. What Git can do is provide alternatives to the "git add <file-name>" command.

Let's assume you've added another three files to the root directory: my-file.ts, another-file.js, and new_file.rb. Now you want to add all of them to the staging area. Instead of adding these files separately, we can add them all together:

All you need to do is type file names separated by spaces following the "add" command. When you run "git status" once more to see what has changed, Git will output a new message listing all the files you've added:

Adding several files to the staging area in one go is much more convenient! But hold on a second. What if the project grows enormously and you have to add more than three files? How can we add a dozen files (or dozens of files) in one go? Git accepts the challenge and offers the following solution:

Instead of listing file names one by one, you can use a period – yes, a simple dot – to select all files under the current directory. Git will grab all new or changed files and shove them into the basket (the staging area) all at once. That's even more convenient, isn't it? But Git can do even better.

There's a problem with the "git add ." command. Since we're currently working in the root directory, "git add ." will only add files located in the root directory. But the root directory may contain many other directories with files. How can we add files from those other directories plus the files in the root directory to the staging area? Git offers the command below:

The option "--all" tells Git: "Find all new and updated files everywhere throughout the project and add them to the staging area." Note that you can also use the option "-A" instead of "--all". Thanks to this simple option, "-A" or "--all", the workflow is greatly simplified.

Remember when we told you that you can take things out of your imaginary basket? Git can also take things out of its basket by removing files from the staging area. To remove files from the staging area, use the following command:

In our example, we specified the command "rm", which stands for remove. The "--cached" option indicates files in the staging area. Finally, we pass a file that we want to unstage. Git will output the following message for us:

Let's run "git status" again:

Git is no longer tracking my-file.ts. In this simple way, you can untrack files if necessary. As an alternative to "rm --cached <filename>", you can use the "reset" command:

You can consider "reset" as the opposite of "add".

We've provided enough Git commands to add and remove files to and from the staging area. Now it's time to get familiar with committing files to the local repository.

Here are the most common Git commands you've learned so far:

Committing Changes to Git

Let's start with a quick overview of committing to the Git repository. By now, you should have at least one file tracked by Git (we have three). As we mentioned, tracked files aren't located in the repository yet. We have to commit them: we need to carry our basket with stuff to the lock box. There are several useful Git commands to do (almost) the same: move (commit) files from the staging area (an imaginary basket) to the repository (a lock box).

There's nothing difficult about committing to a repository. Just run the following command:

To commit to a repository, use the "commit" command. Next, pass the "commit" command the "-m" option, which stands for "message". Lastly, type in your commit message. We wrote "Add three files" for our example, but it's recommended that you write more meaningful messages like "Add admin panel" or "Update admin panel". Note that we didn't use the past tense! A commit message must tell what your commit does – adds or removes files, updates app features, and so on.

Once we've run "git commit -m 'Add three files'", we get the following output:

The message tells us that there have been three files added to the current branch, which in our example is the master or the main branch. The "create mode 100644" message tells us that these files are regular non-executable files. The "0 insertions(+)" and "0 deletions(-)" messages mean we haven't added any new code or removed any code from the files. We actually don't need this information; it only confirms that the commit was successful.

So, what have we done so far? We added files to a project directory in the first section. Then we added files to the staging area, and now we've committed them. The basic Git flow looks like this:

- Create a new file in a root directory or in a subdirectory, or update an existing file.

- Add files to the staging area by using the "git add" command and passing necessary options.

- Commit files to the local repository using the "git commit -m <message>" command.

- Repeat.

That's enough to get the idea of Git's flow. But let's get back to committing files. We should mention a great alternative to the standard "git commit -m 'Does something'" command.

When working on a project, chances are you'll modify some files and commit them many times. Git's flow doesn't really change for adding modified files to a new commit. In other words, every time you make changes you'll need to add a modified file to the staging area and then commit. But this standard flow is tedious. And why should you have to ask Git to track a file that was tracked before?

The question is how can we add modified files to the staging area and commit them at the same time. Git provides the following super command:

Note the "-a" option, which stands for "add". Git will react to this command like this: "I'll just commit the files immediately. Don't forget to write a commit message, though!" As we can see, this little trick lets us avoid running two commands.

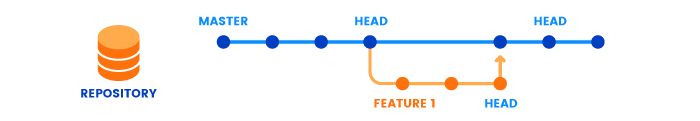

There will be times when you'll regret committing to a repository. Let's say you've modified ten files, but committed only nine. How can you add that remaining file to the last commit? And how can you modify a file if you've already committed it? There are two ways out. First, you can undo the commit:

As you may recall, the "reset" command is the opposite of the "add" command. This time, "reset" tells Git to undo the commit. What follows "reset" is the "--soft" option. The "--soft" option means that the commit is canceled and moved before HEAD. You can now add another file to the staging area and commit, or you can amend files and commit them.

To understand what that "HEAD" thing represents, recall that we work in branches. Currently we're in the master branch, and HEAD points to this master branch. When we switch to a different branch later, HEAD will point to that different branch. HEAD is just a pointer to a branch:

What you see in the image is that each dot represents a separate commit, and the latest commit is at the top of the branch (HEAD). In the command "git reset --soft HEAD^" the last character "^" represents the last commit. We can read "git reset --soft HEAD^" as "Undo the last commit in the current branch and move HEAD back by one commit."

Instead of resetting the HEAD and undoing the last commit, we can rectify a commit by using the "--amend" option when committing to a repository. Just add the remaining file to the staging area and then commit:

The "--amend" option lets you amend the last commit by adding a new file (or multiple files). Using the "--amend" option, you can also overwrite the message of your last commit.

Think of this command in this way: you took out the top stack of papers from the drawer and "amended" them by simply unstapling the bunch of papers, adding another paper, file-i-forgot-to-add.html, on top and rewriting the message on the "commit" paper.

By this time, you've done some work with Git on your computer. You've created files, added them to the staging area, and committed them. But these actions only concern your local repository. When working in a team, you'll also use a remote repository. What are the basic Git commands to work with remote repositories? The answer is in the following section.

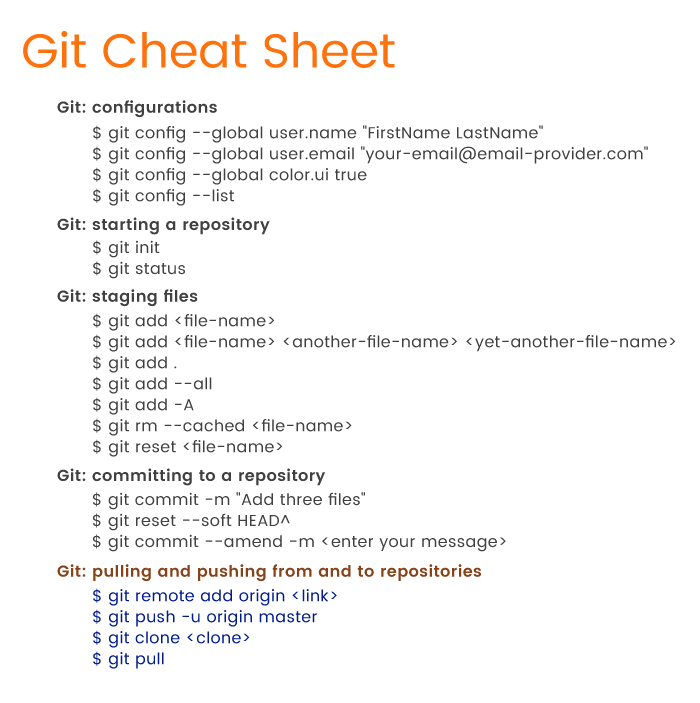

As a summary, so far you've learned the following Git commands:

Push and Pull To and From a Remote Repository

In real development, your workflow will look like this:

- You work on a feature and commit files to a branch (master or any other branch).

- You push commits to a remote repository.

- Other developers pull your commits to their computers to have the latest version of the project.

You'll use several important Git commands to move (push) your code from a local repository to a remote repository and to grab (pull) your team's collective code from a remote repository.

Git has a "remote" command to deal with remote repositories. But before we jump into an explanation of how the "remote" command works, we have to do a little bit of setup.

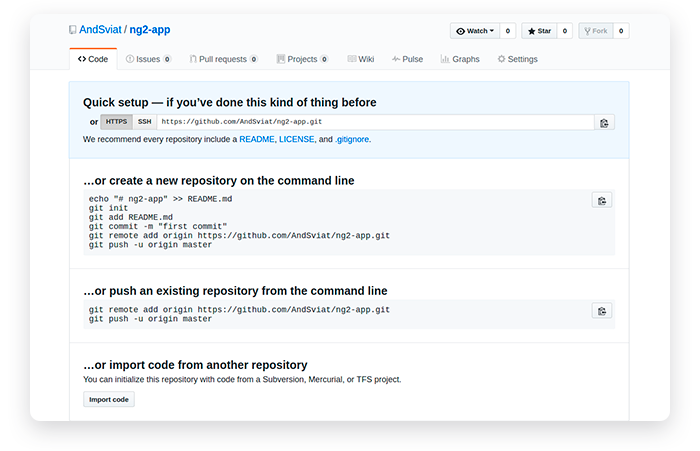

First things first, you need to create a remote repository. We'll use GitHub for this section. You can create an account on GitHub and create a new repository for your project. Just start a project and give it a name. You then need to grab the HTTPS link to this new repository. The link will look similar to this – https://github.com/YourUsername/some-small-app.git – where YourUsername will be your GitHub username and "some-small-app.git" will be the name of your app.

Now you need to bind this remote repository to your local repository:

We tell Git to "add" a repository. The "origin" option is the default name for the server on which your remote repository is located. Lastly, there's a link to your project on GitHub.

Once you run the command above, Git will connect your local and remote repositories. But what does this liaison actually mean? Can you already access your code online? Unfortunately, not yet.

All you did for now is signed papers so that the remote lock box (GitHub) can accept various items (your code) from your home drawer (local repository). To actually copy your things to a remote lock box, you need to personally carry them to it. With Git, copying your code to a remote repository looks like this:

It's obvious that the command "push" tells Git to push your files to a remote repository. What we also specified is the server our local repo is connected to (origin) and the branch we're pushing, which is master. There's also that strange "-u" option. What it means is that we're lazy enough not to run a long "git push -u origin master" command each time we push code to the cloud. Thanks to "-u", we can run only "git push" next time!"

Once you've pushed changes to a remote repository, you can develop another feature and commit changes to the local repository. Then you can push all changes to the remote repository once again, but using only the "git push" command this time around. As we can see, Git tries to simplify things as much as possible.

Is this the happy ending? Not yet. Once you push code to a remote repository, you have to enter your username and password registered with that remote repository.

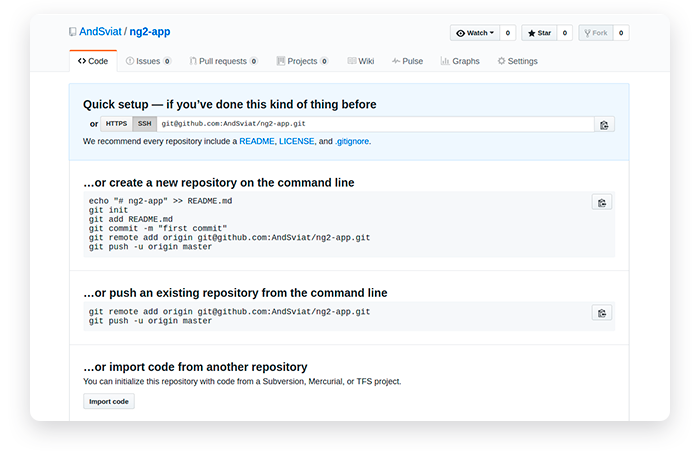

The current problem with "git push" is that you have to enter your credentials each time you push code to GitHub. That's not convenient. The root of this problem is the HTTPS link you used to connect repositories. Git offers a way out of this inconvenience, however.

Let's get back to the page where GitHub offered a link to our project:

As we can see, there's an SSH option that we can use instead of HTTPS. If you set up Git on your computer to work with SSH, then you won't have to enter GitHub credentials every time you push code to GitHub. You'll only need to add a remote origin with this SSH link, like this:

As you can see, to connect repositories via SSH we only changed the link. Keep in mind that HTTPS is the default protocol used for connecting with GitHub, and you need to manually set up SSH.

Now that you've added a remote repository, you can view the list of repositories by running the following command:

The "-v" option will list all remote repositories you've connected to. This is what we've got:

So far we've talked about how to move your things to a remote lock box. Let's say your drawer with all your valuables has disappeared from your home. Now you want to get your things back from the lock box, kind of like cloning them. Git can clone an entire project from a remote repository. That's what the "clone" command does:

"clone" is a simple command. We only need to pass it a link to the GitHub project. We've used an SSH link, but you can use the HTTPS link with the same command.

What "git clone" does is it copies the entire project to a directory on your computer. The directory will be created automatically and will have the same project name as the remote repository.

If you don't like the name of the repository you're cloning, just pass your preferred name to the command:

So far, you've pushed your changes from a local repository to a remote repository and cloned a remote repository. We haven't said anything about the "pull" command, though. Pushing changes to GitHub or BitBucket is great. But when other developers push their changes to a remote repository, you'll want to see their changes on your computer. That is, you'll want to pull their code to your local repository. To do so, run the following command:

Running "git pull" is enough to update your local repository.

Wait, but you said I could clone a repository. Why do I have to pull something?

That's a valid question, so let's clarify.

Cloning a repository is very different from pulling from a repository. If you clone a remote repository, Git will:

- Download the entire project into a specified directory; and

- Create a remote repository called origin and point it to the URL you pass.

The last item simply means that you don't need to run "git remote add origin [email protected]:YourUsername/your-app.git" after cloning a repository. The "clone" command will add a remote origin automatically, and you can simply run "git push" from the repository.

When you run the "pull" command, Git will:

- Pull changes in the current branch made by other developers; and

- Synchronize your local repository with the remote repository.

The "pull" command doesn't create a new directory with the project name. Git will only pull updates to make sure that your the local repository is up to date.

Basically, that's all you need to know about pushing, pulling, and cloning with Git. One set of basic Git commands is left, though. Remember how we mentioned branches in the beginning of the article? Why do we ever need branches? And what are the basic Git commands to view, add, and delete branches? Let's find out.

The Git cheat sheet continues to grow:

List of Git Commands for Working with Branches

You'll use multiple branches for your projects. Branches are, arguably, the greatest feature of Git, and they're very helpful. Thanks to branches, you can actively work on different versions of you projects simultaneously.

The reason why we use branches lies on the surface. If you have a stable, working application, you don't want to break it when developing a new feature. Therefore, it's best to have two branches: one branch with a stable app and another one for developing features. Then again, when you complete a feature and it seems to be working, some bug may still be there. And bugs must not appear in a production-ready version. Thus, you'll want to have another branch for testing.

In the simplest terms, you'll use branches to store various versions of your project: a stable app, an app for testing, an app for feature development, and so on. Actually, what we've described is just one possible way (but certainly not the only way) to organize branches.

How many branches you use and when you should create branches is subject to discussions within a web development team. Before starting a project, developers should decide how and when to create branches and then follow established rules until the project is complete.

Managing branches in Git is simple. Let's first see our current branches:

That's it: one command, "branch", will ask Git to list all branches. In our app, we have only one branch – master. But an application under development is far from being complete, and we need to develop new features. Let's say we want to add a user profile feature. To create this feature, we need to create a new branch:

Again, it's very simple: the "branch" command creates a new branch with the name we gave it: "user-profile". Can we write code for our new feature right away? Not yet!

Let's run the "git branch" command once more:

The output will be the following:

Note the asterisk to the left of "master." This asterisk marks the current branch you're in. In other words, if you create a branch and start changing code right away, you'll still be editing the previous branch, not the new one. After you've created a new branch to develop a feature, you need to switch to the new branch before you get to work on a feature.

For switching branches in Git, you won't use a "switch" command, as you might think. Instead, you'll need to use "checkout":

Git also notifies you that you've switched to a different branch: "Switched to branch 'user-profile'". Let's run "git branch" once more to prove that:

Hooray! You can now freely change any file, create and delete files, add files to the staging area, commit files, or even push files to a remote repository. Whatever you do under the user-profile branch won't affect the master branch.

But wait! You're saying that I can do whatever I need in a new branch and it won't change the master branch at all. But once I finish developing a feature, how can I move it from that development branch to the master? Do I need to copy-paste?

Before we answer the questions, let's first take a look at the flow when adding new branches:

- Create a new branch to develop a new feature using "git branch <branch-name>".

- Switch to the new branch from the main branch using "git checkout <branch-name>".

- Develop the new feature.

You're stuck on the third step. What should you do next? The answer is simple: you need to use the "merge" command. To merge a secondary branch into the main branch (which can be a master, development, or feature branch), first switch back to the main branch. In our case, we should checkout the master branch:

The current branch is now changed to master, and we can merge the user-profile branch using the command "merge":

Keep in mind that you're in the main branch and you're merging another branch into the main – not vice versa! Now that the user-profile feature is in the master branch, we don't need the user-profile branch anymore. So let's run the following command:

With the "-d" option, we can delete the now unnecessary "user-profile". By the way, if you try to remove the branch you're in, Git won't let you:

Let's mention a simpler command for creating new branches than "git branch <name>". Given that you're in the main branch and you need to create a new branch, you can just do this:

But instead of running two commands you can run only one:

This one command will let you create a new "admin-panel" branch and switch to that branch right away. Git earns another point for improving the workflow.

Here's an extensive list of the most used Git commands with examples:

A Quick Recap

Git is a great tool to aid your development process.

From the point of view of web developers, Git is a huge heap of commands. There are dozens of Git commands you should know. But for a start, it's enough to familiarize yourself with the most basic Git commands that we've provided in our tutorial so you can:

- Register your username and email with local repositories

- Initialize a local repository

- Add and remove files to and from the staging area

- Commit changes to the repository

- Undo commits

- Copy your repository to a remote server such as GitHub or BitBucket

- Control the development flow by managing branches.

Solid knowledge of the basic commands for the features listed above is enough for beginners. Try these basic Git commands for yourself and you'll see that the devil isn't as black as he's painted.